An Area of Passage & the Beginnings of Burgundy Terroir

Burgundy’s geology isn’t just background scenery — it’s the reason the vineyards are where they are, and why the wines taste like nowhere else.

If you want to travel north-to-south through western Europe, you pass through Burgundy. For thousands of years, the easiest routes have run right through this corridor — the same paths that became today’s autoroutes and the TGV.

So it’s not surprising that vines took root here. People moved through, and they brought the vine with them — especially the Romans. What is surprising is how well the vine ultimately adapted. Burgundy’s growing season is short and cool, far from the conditions the Romans would have considered natural for ripening grapes.

Finding varieties that truly belonged here took time: centuries of monastic ora et labora, plus at least one royal edict, before the region settled into the core grapes we associate with Burgundy today — above all Pinot Noir and Chardonnay.

Once the varieties were established, Burgundy’s wines gained notoriety quickly. And here’s the twist: many of the earliest settlements — built along the road from the plain toward higher ground — ended up sitting beside some of the best vineyards.

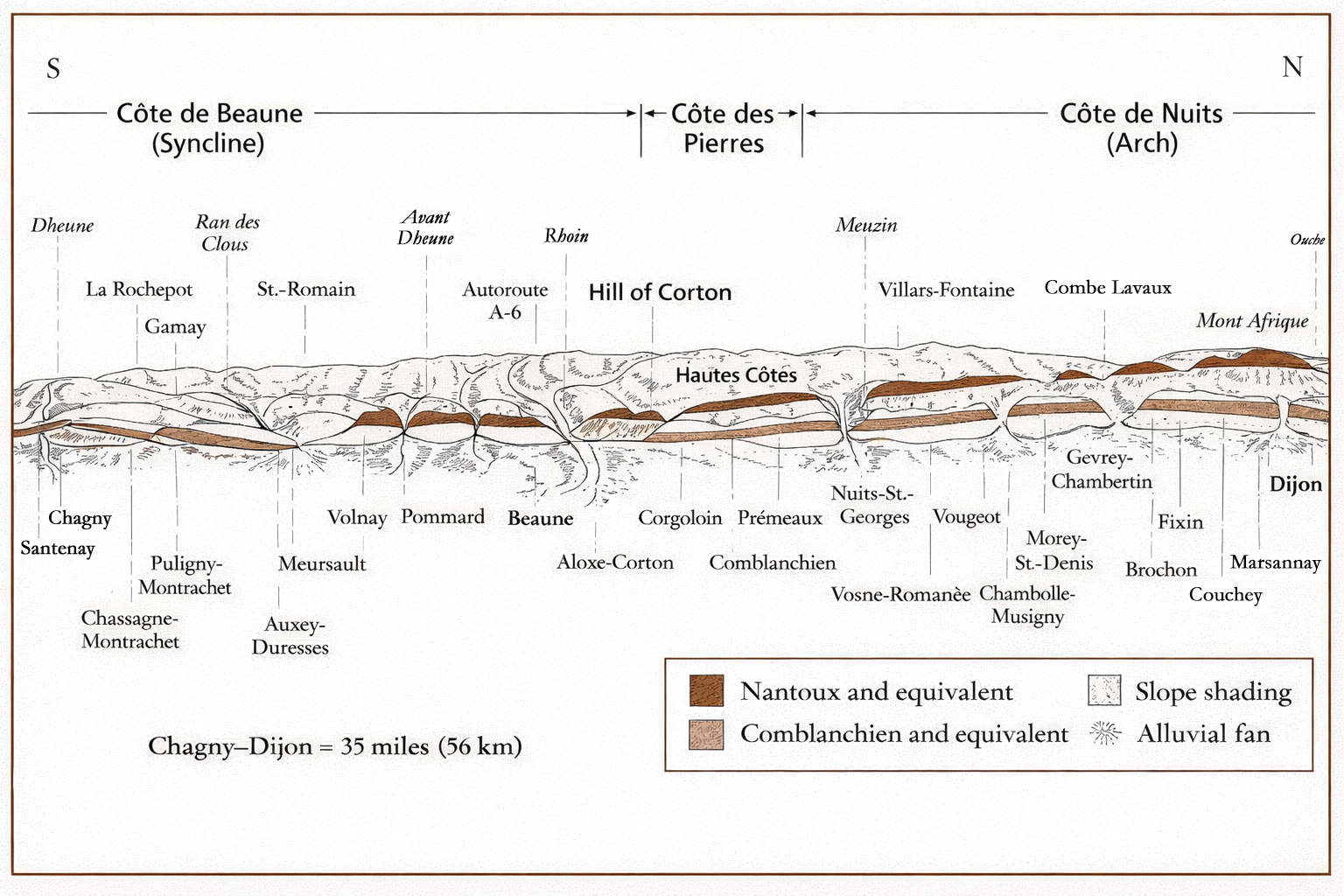

Look closely at the hills behind the villages of the Côte de Nuits and the Côte de Beaune. You’ll notice small valleys cutting up through the slope. The French call these valleys a combe, and nearly every village has one. These breaks in the hillside aren’t just pretty geography — they’re part of the mechanism that created the patchwork of soils, exposures, and water movement that define Burgundy’s “climats.”

Think of the Côte like a series of long rock “sheets,” interrupted and reshaped by combes and broader valleys. From Gevrey-Chambertin down to just south of Nuits-Saint-Georges, you can read a largely continuous band — the spine of the Côte de Nuits. Then that structure dips away.

From Ladoix down to just south of Volnay, another major band appears — broken by combes and, most dramatically, the wider valley behind Corton. This is the northern heart of the Côte de Beaune.

And then, just south of Volnay, something remarkable happens: the band that disappeared near Nuits-Saint-Georges returns. This is where the “golden triangle” of white Burgundy begins — Meursault, Puligny-Montrachet, and Chassagne-Montrachet — all connected, geologically, to the same underlying story as the great reds further north.

Turn back toward the hillside again. In places, there’s no combe — or none to speak of. Instead you see cliffs, like those of Saint-Romain: cliffs that didn’t crumble and spread silts into the plain in the same way. That difference — erosion here, stability there; rubble here, clean breaks there — is the essence of terroir in Burgundy, and a visual explanation for why the climats fall where they do.

Further reading: Terroir, the Role of Geology